An air of mystery surrounds the development of the medieval fiddle from the first appearance of the bow in tenth-century religious iconography of Spain to its widespread popularity in Europe by the thirteenth century. The use of stringed instruments (chordophones), both within and outside of religious practice, is well documented around the ancient globe. For example, the Greek lyre, Persian chang and Chinese guqin all made significant contributions to musical culture, but they are each played by plucking the strings. The bow is a relatively new technology that scholars such as Werner Bachman speculate arrived in the west from central Asia by way of either the Byzantine or the Arabic empires.[1]

The earliest written reference to the bow comes from nineth-century Persian geographer Ibn Khurradadbih who writes that the bowed Byzantine lira is similar to the Arab rebab.[2] The earliest image of the bow comes from a Spanish manuscript circa 920, the Beati in Apocalipsin libri duodecim (see Figure 1). These four large bottle-shaped fiddles are being played by a semi-circular bow in the hands of the Elders of the Apocalypse from the book of Revelation. Approximately a century later, these same characters, as well as King David from the Old Testament, began to be featured in sculpted forms in Romanesque cathedrals along the Camino de Santiago.

Figure 1: Beato de Liébana, Beati in Apocalipsin libri duodecim (c. 901-1000), Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, Vitrina 14-1, fol. 130

David is a popular figure in medieval Christian iconography because of his position within the genealogy of Jesus, and his status of a king bolsters the authority of church patrons who raised or donated the funds for the construction of these monuments. Three stages of David’s life are typically represented in Romanesque cathedral sculpture. The most common are David as a beardless youth fighting Goliath, David as a king playing a chordophone, and David with Bathsheba. The musical instrument David played in the Old Testament was the Hebrew kinnor (כִּנּוֹר) which is usually translated into English as harp or lyre. Since the bow did not exist during David’s lifetime, it is striking to see David depicted with a contemporary instrument on so many of these Romanesque churches.

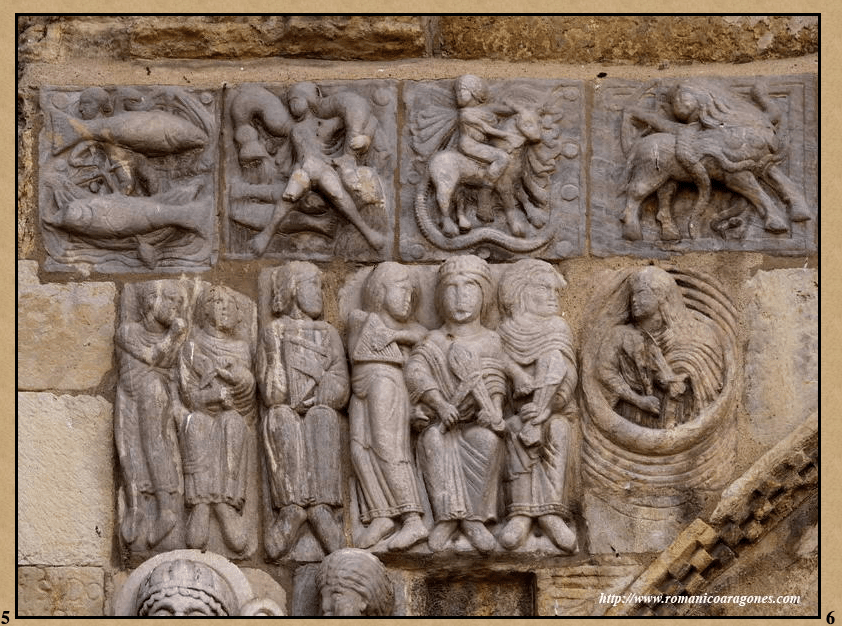

As pilgrims travel along the Camino in northern Spain, they might stop in the northwest province of León at the Basilica de San Isidoro. The relief of David at the south portal shows him playing the fiddle among several fellow musicians (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: King David with musicians and the signs of the zodiac, Basilica de San Isidoro, León

The figure of David is slightly foregrounded, looking forward at the viewer. He wears a crown and the position of the bow positioned on the strings of the fiddle suggests that he is playing the instrument. The other instrumentalists all face left toward the portal, except one fiddler on the right end on the line, who faces left toward the ensemble. This musician is playing the fiddle inside of a mysterious ringed tunnel, and a similar figure is mirrored on the opposite side of the door. While several scholars have published interpretations of the Angus Dei tympanum above this portal, I have yet to find any scholarship specifically interpreting this ringed tube image.[3]

I have two theories of what the San Isidoro image might mean. First, the rings of the tube suggest movement, therefore, the fiddler could represent the connection between music and dance. David famously danced in spiritual ecstasy before the Ark of the Covenant as it was carried into his newly built capital, Jerusalem (2 Samuel 6:14-16).

Sculptures from other Romanesque churches give the nickname “Dance of David,” like La Daurade, Haute-Garonne, in Toulouse and the monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll, Spain. The southern portal at Santa Maria de Uncastillo (Figure 3) is especially interesting because the central figure of the arch is an acrobat standing on his head rather than a dancer. The figure holding the fiddle, slightly to the left of the acrobat, has only recently been identified as King David. I propose that the acrobat could also be a representation of David as he “leaps” and dances before the Ark. While these images of the “dance of David” are not similar visually to the ringed tube at San Isidoro, I posit that the circular motion of rings could suggest dance or movement because of the close connection of music and dance in David’s life.

Figure 3: King David with fiddle next to an acrobat and harpist, Santa Maria de Uncastillo

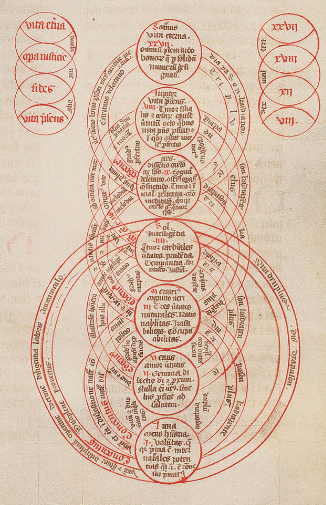

My second theory about the fiddler in the ringed tube at San Isidoro pertains to the role of music in medieval cosmology and the close placement of the David’s ensemble near signs of the zodiac on the cathedral.[4] In his treatise, De institutione musica, the late-Roman philosopher, Boethius, credits Pythagoras with the ability to hear revolving planets emitting their own pitch.[5] As a mathematician, Pythagoras calculated the ratio between these pitches as the “perfect” harmonic intervals: the octave (2:1), the fifth (3:2), and the fourth (4:3). Sometimes referred to as the “harmony of the spheres,” this musical cosmology creates a bridge between the astrological signs of the zodiac above the portal and the image of David, as the personification of music. I have not yet found any other medieval sculptures that share this ringed motion. However, there several manuscript illuminations of musical cosmology that come close. Figure 4 is a zoomorphic design of Boethius’ monochord, a string instrument he used to teach the perfect intervals. The overlapping semi-circles show the distance between pitches visually indicating where one would place a finger on the string for each pitch.

Figure 4: Boethius, De Musica, Zoomorphic diagram of the perfect intervals, Turnbull MSR 05, fol. 58r

Figure 5 is an image of the harmony of the spheres depicting the seven “planets” or celestial bodies including the sun and the moon. Each planet is represented by a circle and the descending nature of their circular orbits is similar to the San Isidoro fiddlers’ ringed tube.

Figure 5: De anima mundi et de concordia planetarium by Lambert of St. Omer in Liber Floridus, The Hague, KB, 72 A 23, fol. 216r

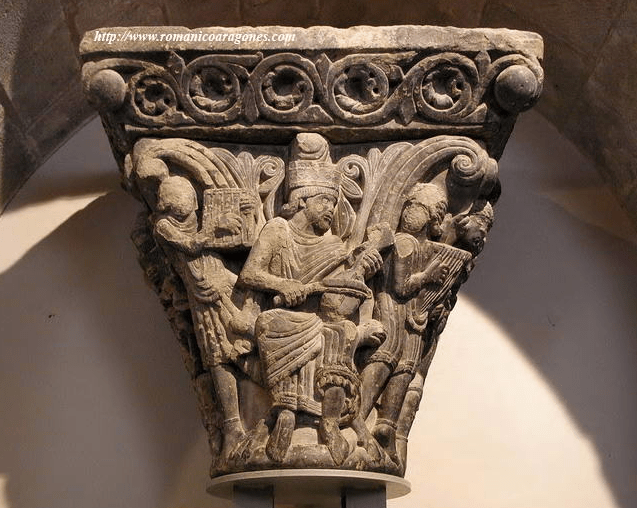

The second church on the Camino where a pilgrim will encounter a fiddling King David is at San Pedro Cathedral of Jaca, Huesca in the northeast of Spain. This David, positioned on a capital at the top of a column of the south portal, wears a crown and sits on a throne holding his fiddle in playing position on his knee (see Figure 6). Animal heads are carved into the arms of the throne, and the legs of the throne are animal’s feet. Martinez interprets this as David’s dominion over beasts suggesting beasts are equivalent to evil.[6] However, David grew up as a shepherd honing his sling-shot skills on wild lions and bears before the famous confrontation with Goliath. Therefore, I would argue that concept of dominion over beasts on the throne are just as likely meant to be animals.

Figure 6: Fiddling King David and musicians at San Pedro Cathedral of Jaca, Huesca

The capital contains eleven other musicians in addition to David, and the number twelve is significant in the Old Testament as representative of the twelve tribes of Israel. These musicians are playing several different musical instruments: horns, panpipes, portative organ, drums, and harp. Some of these instruments, like the portative organ and bowed fiddle were new technologies in the Middle Ages; other instruments correspond historically to 1 Chronicles 15:16-22, where David commands the Levites to “make a joyful sound with musical instruments: lyres, harps, and cymbals” (וַיֹּ֣אמֶר דָּוִיד֮ לְשָׂרֵ֣י הַלְוִיִּם֒ לְהַֽעֲמִ֗יד אֶת־אֲחֵיהֶם֙ הַמְשֹׁ֣רְרִ֔ים בִּכְלֵי־שִׁ֛יר נְבָלִ֥ים וְכִנֹּרֹ֖ות וּמְצִלְתָּ֑יִם מַשְׁמִיעִ֥ים לְהָרִֽים־בְּקֹ֖ול לְשִׂמְחָֽה׃ פ).[7] Many ancient Hebrew words fell out of use and the meaning has been lost, for example, “stringed instrument” (ְבָלִ֥ים) is vague, and organologists lack the iconographic evidence to unpack what these words mean.

San Pedro’s David plays the fiddle in a downward position resting on the left leg, the “eastern” playing position used with instruments like the Arab rabab. In the west, the Greek lira was more typically played on the shoulder, while in Byzantium both techniques appear in the iconography.[8] If the original placement of this David was on a capital in the Cathedral’s choir, as some scholars claim, the context is easy to ascertain.[9] One of the duties of a monastic choir was to sing through the book of Psalms during the canonical hours—many of the Psalms are attributed to David.

Two similar capital sculptures can be found in France at the Monastery of Notre-Dame de la Daurade in Toulouse, and the Abbey of St. Pierre in Moissac. At Notre-Dame de la Daurade, King David is seated, positioned on the left corner of the capital, playing the fiddle on his shoulder (see Figure 7). Four other musicians surround him playing a round frame drum, triangular harp, and perhaps cymbals or bells (the sculpture in too degraded to identify). The number four is also significant for Christianity as David the son of Jesse is part of Jesus’ genealogy, likewise the four musician point to the coming of the four Evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Figure 7: King David and four musicians at Notre-Dame de la Daurade, Toulouse France

The capital of King David at St. Pierre, Moissac also has four musicians along with inscriptions of their names: Ethan, Idithun, Asaph, and Heman. These names can be found in 1 Chronicles chapters 6 and 25, which describe David assigning members of the tribe of Levi to take charge of providing music for the tabernacle where the Arc of the Covenant was kept until Solomon built the first Temple in Jerusalem.

Figure 8: Capital of David, Ethan, Idithun, Asaph, and Heman—South Side of St. Pierre, Moissac

The final stop for the pilgrim is at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela which boasted the final resting place of the apostle James. Here, the relief of King David has been relocated to the left buttress of the Platerías façade near the southwest portal (Figure 9). His original placement was on the gate at the north transept which was called the “Franígena Gate” because the pilgrims from France entered there. This gate was destroyed in 1757 due to disrepair and several of the reliefs relocated. The original program at the north gate is described in the Codex Calixtus and addressed the Creation and the promise of Redemption. David’s role in this message is as an ancestor of Jesus, foretelling the coming of Christ.[10]

Figure 9: King David with fiddle at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

Martinez writes that the relief was made around 1103 by the great Romanesque sculptor “Maestro de Eva,” in a style informed by classical principles undergoing sharp geometrization.[11] David’s head is turned outward (toward the center of its original façade), seated with feet crossed. This seating position is similar to the Kind David sculpture at Church of Saint Sernin in Toulouse (Figure 10). The similarities suggest a contemporaneous influence, but scholars do not know which one was the first. Much of the early scholarship assumes the French churches were first but more recent scholars call this into question.[12] One important difference between the Saint Sernin sculpture and Santiago de Compostela is the placement of the bow and instrument. The former David holds the instrument on his knee and the bow upwards with the hair-side turned away from the instrument. At Santiago de Compostela, David holds the fiddle on his shoulder with the hair-side of the bow near the strings, as if he had been playing but got distracted by something in the distance.

Figure 10: Kind David at Church of Saint Sernin in Toulouse

I chose to build my own version of the Santigo de Compostela fiddle because of the prominence of Santiago de Compostela as the destination of the Camino, and the size and quality of the sculpture which I noted when I visited Spain in the summer of 2022. The construction of this fiddle matches Curt Sachs description of a Byzantine lira “pear-shaped, shallow slightly bulging body, without a distinct neck, ending in a disk or box with three rear pegs.”[13] Sachs was an early well-renowned scholar of musical instruments (organologist), and his work is likely the reason Martinez calls all of the fiddles in her article Byzantine liras. Other scholars refer to the Santiago instrument as a rebec, named after the Arabian rabab traceable to eleventh century Spain. The most prominent distinction between the lira and the rabab, according to Sachs, are the lateral facing pegs (like the modern violin) and the sickle-shaped peg box (see Figure 11). Since there is so much variety in size and shapes of instruments throughout the Middle Ages, I chose to call these instruments by the more comprehensive term “fiddle.”

Figure 11: Moorish rebab from the Cantiagas de Santa Maria, Códice J.B.2

Other features of the Santiago fiddle that I tried to copy are the leaf-shape tailpiece, the flat bridge, and the rear facing pegs. While virtually nothing is known about the materials out of which these instruments were constructed, modern stringed instruments are typically made from hard woods like cedar or mahogany. I found an affordable block of red oak at CU Woodshop Supply, and I attempted to use similar measurements of David’s fiddle. I did decide to narrow the neck of the instrument to make it easier to reach all the strings with the left hand.

Eventually, I would like to expand this research to locate more example of Romanesque cathedrals with King David and the fiddle. By the thirteenth century, the fiddle becomes the most popular medieval instruments played by both professional musicians and aristocratic armatures like the troubadour, Baron Pons de Capdoill. My hypothesis is that Romanesque architecture supported the dissemination of this instrument to other countries along the pilgrimage route. Although much more research is needed to make this a convincing argument.

[1] Werner Bachmann, The Origins of Bowing and the Development of Bowed Instruments up to the Thirteenth Century (Oxford University Press, 1969).

[2] Henry George Farmer, Historical facts for the Arabian Musical Influence (Ayer Publishing, 1988), 137.

[3] This tyampanum is called “Angus Dei” because it features a lamb and a cross as a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice. Below the lamb is a scene depicting the Old Testament story of Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac at God’s request, but he is stopped by God who provides a sacrificial ram for a burnt offering instead. Ishmael and Hagar flee the scene to the right of the portal. Ishmael is dressed in medieval Arabic clothing, riding a horse with a bow and arrow which scholars have interpreted as promoting the reconquest of Christian kingdoms in Spain over the Muslim empire during this period. Doron Bauer, “Social Practices and the Romanesque Architectural Sculpture in the Pyrenees,” PhD diss. (Johns Hopkins University, 2012), 50.

[4] This was not the original placement of the signs of the zodiac, but their relocation can also point to a new narrative program for this portal. José Alberto Moraís Morán discusses the relationship between cosmology and music in his article, “La Efigie Esculpida de Rey David en Su Contexto Iconográfico. Una Poética Musical Para la Apotheosis Celestial en la Portada Del Cordero de San Isidoro de León,” In Imáges del Poder en la Edad Media Tomo II, 355-375 (University of Leon, 2011). However, Morán does not address other images from manuscripts of Boethius’ De institutione musica.

[5] Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, Fundamentals of Music, trans. by Calvin M. Bower (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 5.

[6] Rosario Alvarez Martinez, “Music Iconography of Romanesque Sculpture in the Light of Scultures’ Work Procedures: The Jaca Cathedral, Las Platerías in Santiago de Compoestela, and San Isidoro de Leon,” Music in Art 27 (2002): 19.

[7] Westminster Leningrad Codex, Chronicles 15:16.

[8] Curt Sachs, The History of Musical Instruments (W.W. Norton, 1940), 275.

[9] See Martinez, “Music Iconography of Romanesque Sculpture,” 35n28.

[10] Rosario Alvarez Martinez, “Music Iconography of Romanesque Sculpture in the Light of Scultures’ Work Procedures: The Jaca Cathedral, Las Platerías in Santiago de Compoestela, and San Isidoro de Leon,” Music in Art 27 (2002): 13-36, 27.

[11] Martinez, “Music Iconography,” 28.

[12] Martinez, “Music Iconography,” 29.

[13] Sachs, The History, 275.